Ali Cherri: If you prick us, do we not bleed?

Herbert Art Gallery & Museum

12 August 2022 - 8 January 2023

Lebanese artist Ali Cherri presents a series of mixed media, sculptural installations which consider how histories of trauma can be explored through a response to museum and gallery collections. Developed during a recent residency at the National Gallery, the artworks respond to five paintings that were vandalised while on display, and how these attacks were perceived and described.

The exhibition If you prick us, do we not bleed? began with research in the The National Gallery’s archive, from which Cherri uncovered accounts of five National Gallery paintings that were vandalised while on display. He was struck by the public’s highly emotional response to these attacks, finding that newspaper articles would describe the damages as if they were wounds inflicted on a living being – even referring to the Gallery’s conservators as surgeons.

He also noticed an overwhelming urge to ‘heal’, make good and hide the damage. This personification of artworks, and the suggestion that they can experience distress, is reflected in the exhibition’s title, taken from Shakespeare’s play The Merchant of Venice.

In response, Cherri presents a series of mixed media, sculptural installations that recall aspects of each painting and that imagine its life following the vandalism. They bring into question what Cherri calls the ‘politics of visibility’; the decisions we make about how, and to what extent, we accept trauma within museums. By translating each damaged work into a series of objects, Cherri’s work highlights, rather than shies away from, the trauma inflicted on them, reminding us that we are never truly the same after experiencing violence.

The Madonna of the Cat, after Barocci (2022)

“The Madonna of the Cat, after Barocci” is inspired by Federico Barocci’s “La Madonna del Gatto”, painted around 1575.

Comprised of a Classical-style, white porcelain hand resting on a taxidermied goldfinch, the sculpture has been purchased for the Herbert' Art Gallery & Museum’s permanent collection by the Contemporary Art Society.

In Barocci’s painting, the young John the Baptist clutches at a goldfinch, while the Madonna, who is nursing the baby Jesus, appears to be warning him to watch out for a cat at her feet which is also eyeing the bird. According to legend, the goldfinch received its bright red markings from a drop of blood that fell from Christ as he carried the cross to his crucifixion.

This work was chosen with its connection to our natural history collection in mind, as well as its religious iconography, which was considered fitting with nearby Coventry Cathedral.

The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne and the Infant Saint John the Baptist (‘The Burlington House Cartoon’), after Leonardo (2022)

Created by Leonardo Da Vinci in the early 1500s, ‘The Burlington House Cartoon’ is a chalk and charcoal drawing was shot in 1987 from a distance of approximately 7 feet.

Cherri’s response is comprised of three sculptures: the central cardboard circle representing a 600% enlargement of the bullet hole in the original drawing; “The all-seeing eye”, a pyramid of 19th century glass prosthetic eyes, and a stack of newspapers from the day of the attack, topped with a copy of John Berger’s Ways of Seeing, in which he writes of the Da Vinci work, "It has acquired a new kind of impressiveness. Not because of what it shows – not because of the meaning of its image. It has become impressive, mysterious because of its market value".

With the newspapers, Cherri encourages us to consider the attack on the painting in its social and political context, while the elevated bullet hole turns trauma into “something that we hold high as a lived experience”, rather than something to be hidden away.

The Toilet of Venus (“The Rokeby Venus”), after Velázquez (2022)

On 10 March 1914, suffragist Mary Richardson walked into the National Gallery, London and attacked Diego Velázquez‘s The Toilet of Venus (known as “The Rokeby Venus”) with a meat cleaver, in protest against the arrest of Emmeline Pankhurst the previous day.

“I have tried to destroy the picture of the most beautiful woman in mythological history as a protest against the Government for destroying Mrs Pankhurst, who is the most beautiful character in modern history,” she said.

For Cherri, Velázquez’s treatment of his subject is surprisingly modern: “Velázquez places the mirror in the centre of the painting, in a way empowering this female figure… She’s like self-sufficient and we become like these intruders looking at her face through the mirror. He drew the face in a very hazy, out of focus way, saying that we will not have access to who Venus really is.”

His response to the work recreates this effect by leaning a Classical-style head against an upturned mirror, with a single glass eye gazing back at us when we look down on it.

For the body, he drew inspiration from Paleolithic “Venus” figurines like the Venus of Hohle Fels, suggesting that violence, “returns [the modern subject] to something more archaic” or “primitive”.

Self-portrait at the age of 63, after Rembrandt (2022)

One of Rembrandt’s last self-portraits, the painting that inspired this work had yellow paint squirted on it at the National Gallery in 1998. The attacker was a young man from Coventry.

Gallery conservators quickly got to work removing the paint, and the painting was back on display - unscathed - the next day.

Cherri’s work imagines the famous portrait in three dimensions, hanging by a single chain, alone and isolated within a kind of double-cage structure, with a metal frame enclosed inside a wooden and glass cabinet.

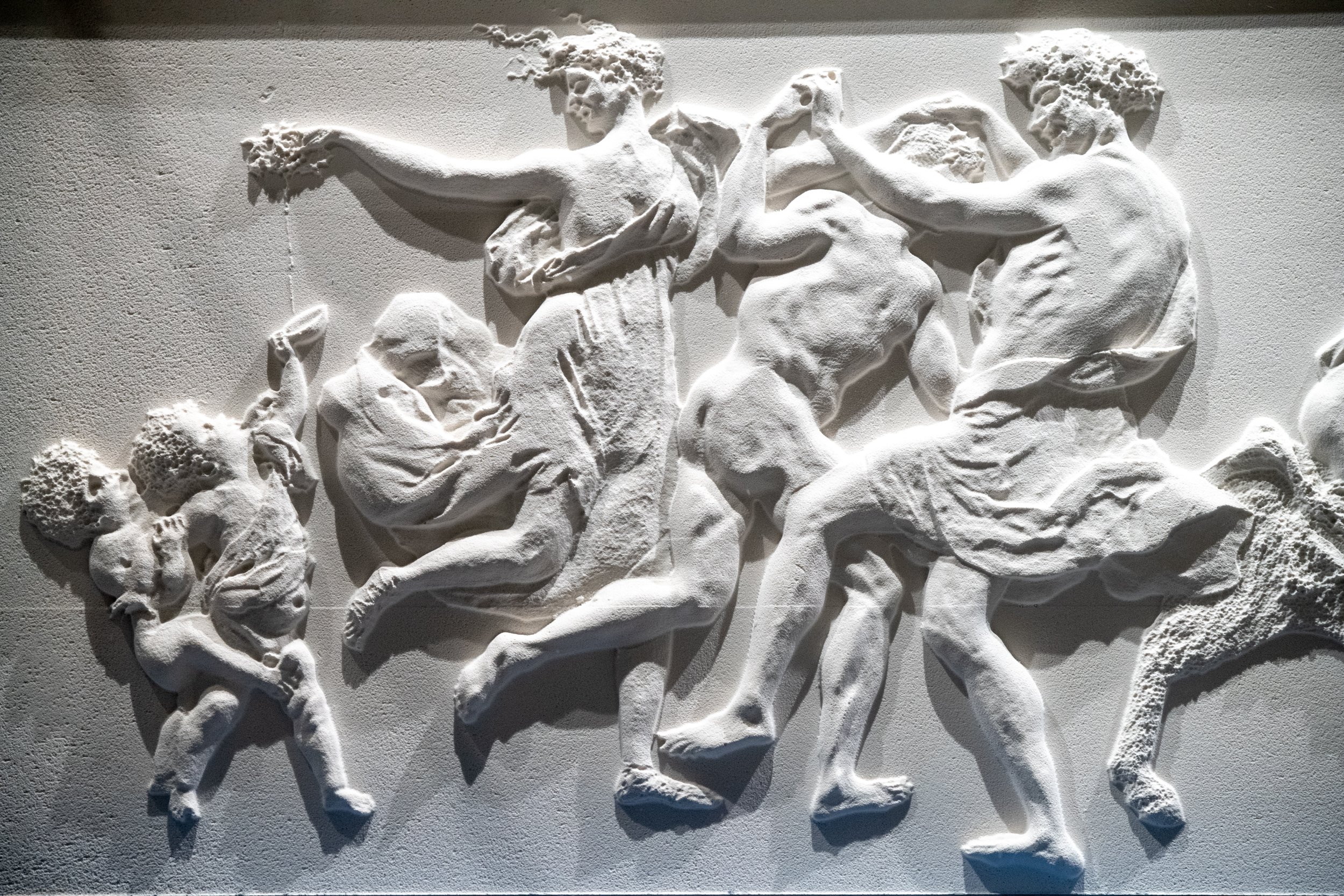

The Adoration of the Golden Calf, after Poussin (2022)

Painted between 1633 and 1634, Poussin’s The Adoration of the Golden Calf depicts a scene from the biblical Book of Exodus, when the Israelites, disheartened by Moses’ long absence on Mount Sinai, began worshipping a golden idol, just before the prophet returned to them with the Ten Commandments.

Cherri’s response focuses on the idol itself, using taxidermied conjoined twin lambs from the 1930s in place of the calf, positioned on top of a gold leaf surface, bathing them in a golden glow. Cherri describes this “eight-legged, two-headed lamb” as a “monstrous figure of the animal… in the etymological sense of the monster as something that doesn’t resemble itself any more”, prompting us to reflect on how the original artwork might be transformed through vandalism.

The bas relief on the plinth nods to the Classical relief sculptures that inspired the dancing figures in Poussin’s painting, bringing the prompt and response full circle in a new sculptural context.

The 2021 National Gallery Artist in Residence is a collaboration with the Contemporary Art Society, generously supported by Anna Yang and Joseph Schull.

Programme sponsored by Hiscox